The purpose of this lab is to set up and test the Bluetooth Communication between the Artemis Nano board and our computer with the given Bluetooth adapter.

To connect to the robot, I first tried running the given Python script natively on MacOS, using MacBook’s Bluetooth module. The result was abysmal. On my first attempt, the program took about 35 tries to find the robot, and on my second attempt, close to 100. Therefore, I decided to use the given USB Bluetooth Adapter. After adding a USB device filter on Virtualbox and setting the bluetoothHostControllerSwitchBehavior option of the non-volatile memory of my laptop, I was able to attach the adapter to the VM and find the robot. I then added the MAC address in settings.py as suggested.

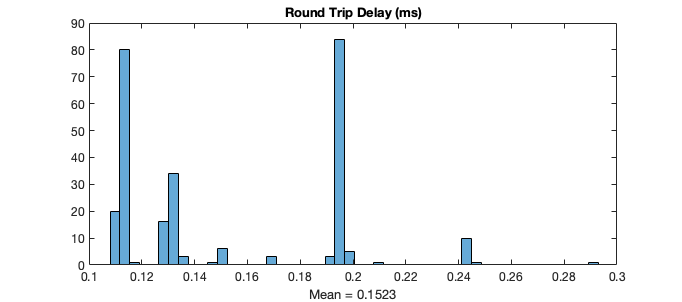

After successfully connecting to the robot, I tried my first command. By uncommenting await theRobot.ping() in myRobotTasks(), I added a task that pings the board. Since pingLoop is set to true in settings.py, the script craetes a new ping request whenever a response from a ping request is received. Therefore, we have a continuous measurement of the round trip time between my laptop and the Artemis Nano.

As we can see from the video below, the RTT starts at about 20ms. After about 20s, however, it drops to approximately 11ms. This is reflected on the histogram as about half the samples were collected after the drop and the other half before. The average delay is therefore in the middle, about 15ms.

Each round trip consists of two packets, each with 99 bytes of data (1 byte for the command type, 1 byte for the data length, and 97 bytes of 0). Since the RTT drops to a steady 11ms, we will use that for our round-trip data rate calculation.

\[ R=\frac{N}{T}=\frac{99\times2\times8\,bit}{0.11\,s}=14400\,bit/s\]

Disappointly, this is much lower than a wired, serial conection.

Another command I tested out was REQ_FLOAT using await theRobot.sendCommand(Commands.REQ_FLOAT). I modified the Arduino code so that when the board receives such requests, it sends a response of command type GIVE_FLOAT, length of 4 (a float has 4 bytes), and a 4-byte data array consisting of the float.

res_cmd->command_type = GIVE_FLOAT;

res_cmd->length = 4;

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) res_cmd->data[i] = ((byte *) &ret_float)[i];

amdtpsSendData((uint8_t *)res_cmd, res_cmd->length + 2);

The process can be seen in the following video.

Obviously, the intention was to send 4.96 back to my laptop. However, the video clearly shows 4.960000038146973 being received. This is due to the limitation of the data type itself. Float has 24 bits of precision, which translates to about 7 decimal places. Indeed, there are five zeros after 4.96. This means that when comparing float values, we cannot simply use operators == and !=.

The last test I conducted was the measurement of the data rate of a byte stream. After sending a START_BYTESTREAM_TX command to the Artemis Nano, it sets the varibale bytestream_active, which results in the board sending a response command with a certain amount of data as fast as possible. To measure how long it takes for the board to send out a message, I record the time before and after each transmission.

unsigned long before, after;

before = micros();

amdtpsSendData((uint8_t *)res_cmd, res_cmd->length + 2);

after = micros();

Serial.printf("Took %d us\n", (int)(after-before));

In addition, I also need to how long it would take for each packet to actually get processed. Therefore, I record the time every time the Python script receives a packet and compare it with the last iteration.

if (code == Commands.BYTESTREAM_TX.value):

print(time.time() - theRobot.now)

theRobot.now = time.time()

One run can be seen from the video below.

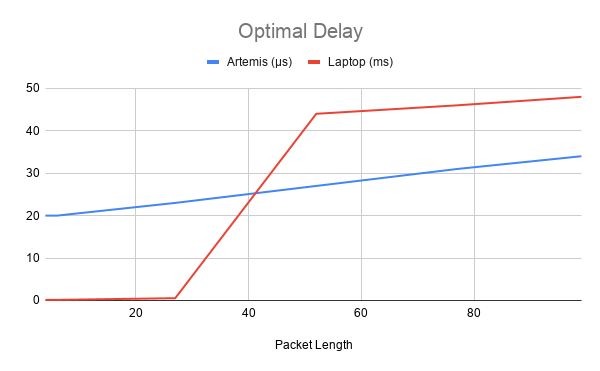

Since we are interested in knowing the theoretical limit as well as the average bandwidth, I compare the minimal time as well as the average time. Timing on the Artemis board is very consistent, and therefore the minimal time can be viewed as the average time. The Python program, however, tells a different story.

First, the theoretical limit.

| Packet Length | 4 | 6 | 27 | 52 | 77 | 99 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min Time on Artemis (μs) | 20 | 20 | 23 | 27 | 31 | 34 |

| Min Time on Laptop (ms) | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.55 | 44 | 46 | 48 |

We can again calculate the data rate just like we did for ping. For example, when sending a command with 2 bytes of data, the Artemis board has the following data rate:

\[ R=\frac{N}{T}=\frac{4\times8\,bit}{20\times10^{-6}\,s}=1.6\times10^6\,bit/s\]

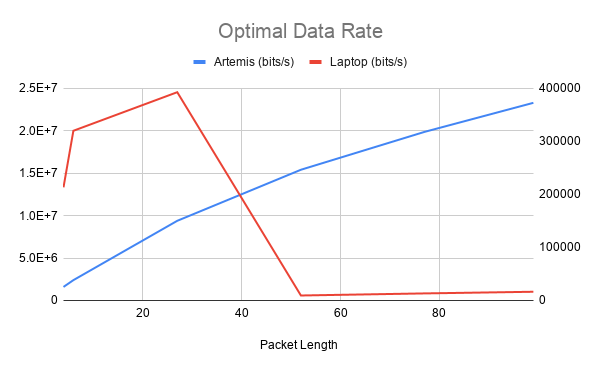

Then, for each entry we calculate the same thing.

| Packet Length | 4 | 6 | 27 | 52 | 77 | 99 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemis (bits/s) | 1600000 | 2400000 | 9391304.348 | 15407407.41 | 19870967.74 | 23294117.65 |

| Laptop (bits/s) | 213333.3333 | 320000 | 392727.2727 | 9454.545455 | 13391.30435 | 16500 |

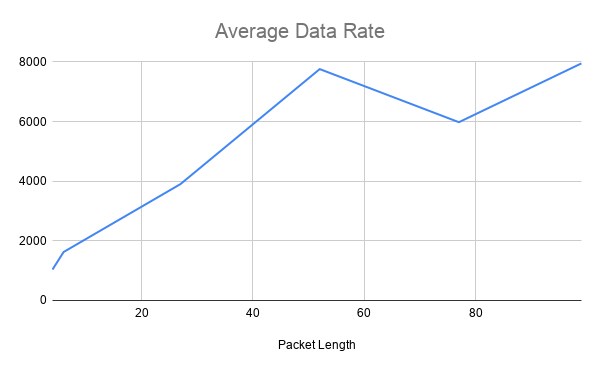

As we can see, on the Artemis board, the data rate increases almost linearly with the packet size. This tells us that the actual transmission time is insignificant to the overhead. As packet size increases, the transmission time barely changes, therefore increasing the data rate. The bottom row is probably more realistic as it not only considers the time for data to transfer, but also be the time to process on both ends. It seems that the data rate follows a similar trend at the beginning, but then decays rapidly. This could be due to the increasing overhead in processing outweighting the benefit we gain from larger packet sizes.

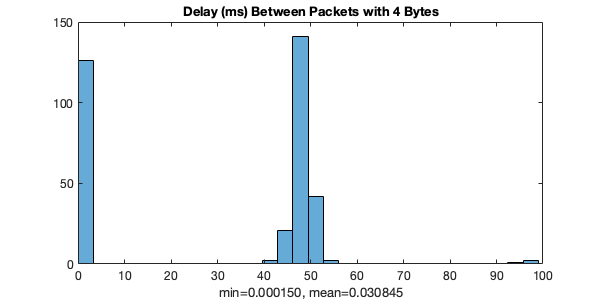

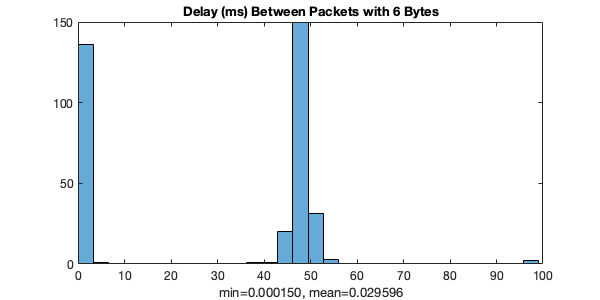

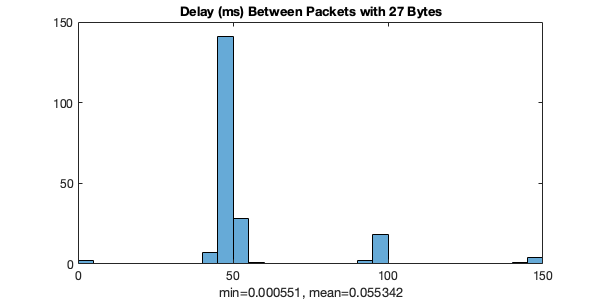

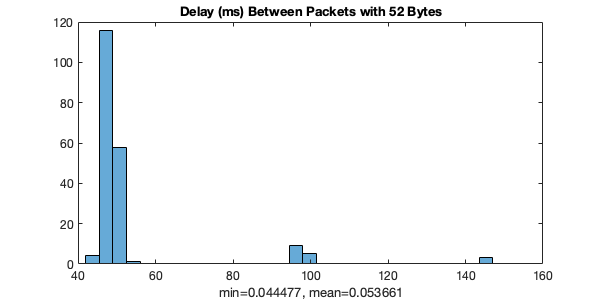

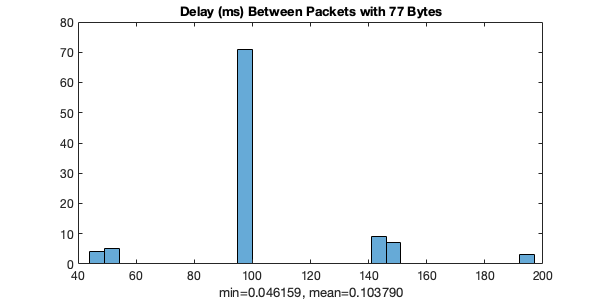

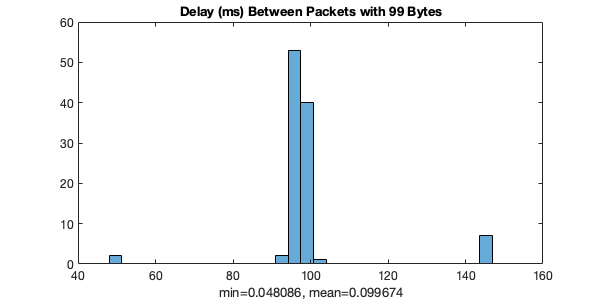

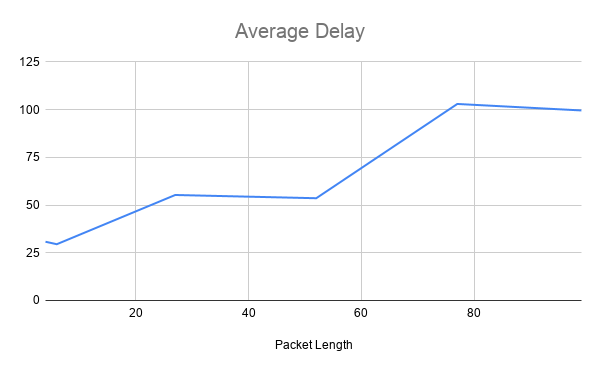

But we are also interested in the average data rate. Therefore, we graph with the following histograms and perform similar calculations on the average time between two packets.

The results are as follows:

| Packet Length | 4 | 6 | 27 | 52 | 77 | 99 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delay (ms) | 30.8 | 29.5 | 55.3 | 53.6 | 103 | 99.6 |

| Bit Rate | 1038.961039 | 1627.118644 | 3905.96745 | 7761.19403 | 5980.582524 | 7951.807229 |

Therefore, realistically, the data rate that we are facing is probably closer to 5000 bps, which is slower than a modem in the early 90s, operating at 9600 bps.